Read Greg Ruth’s previous article, Horror is Good for You (And Even Better for Your Kids).

Horror has a lot to teach us, in terms of narrative, that can be used to tell different kinds of stories—you don’t have to tell scary ones. I’m ignoring the lazy tendency towards shock or gore narratives, which—while technically horror—don’t rate in my book. Jumping out of the closet to spook your little brother for fun can be cute, but it’s hardly rocket science. What we’re here to dive into is the construction of horror narratives. To earn legitimate frights, to build tension and create mood, whether in film, TV, comics, prose, or a single image, requires a lot of thought and planning and elegance in order to do it right. What we can learn from horror begins with the recognition that the tools needed to make it work are tools used in every other kind of story, even romantic comedies. Comedy and Horror are so related to each other, so identical in their construction as to quite nearly be the same thing. Horror just uses these tools in a more precise and specifically sharp manner, so in developing an observational eye for these tricks and tools we can make any kind of story better and more effective.

So let’s look into some simple tips and guidelines…

Fright is not the same as Horror.

Look: anyone can leap out from behind a door and give you a good fright. Children do it all the time, especially in my house. Movies lean on this type of shock like it’s the only working tool in the box and have codified the jump scare so much now that it’s become dull and obvious (though it still manages to startle, even if you find it funny a second later). This is the easiest thing to do onscreen, but in comics, or even in prose, it doesn’t work (to the probable benefit of both mediums).

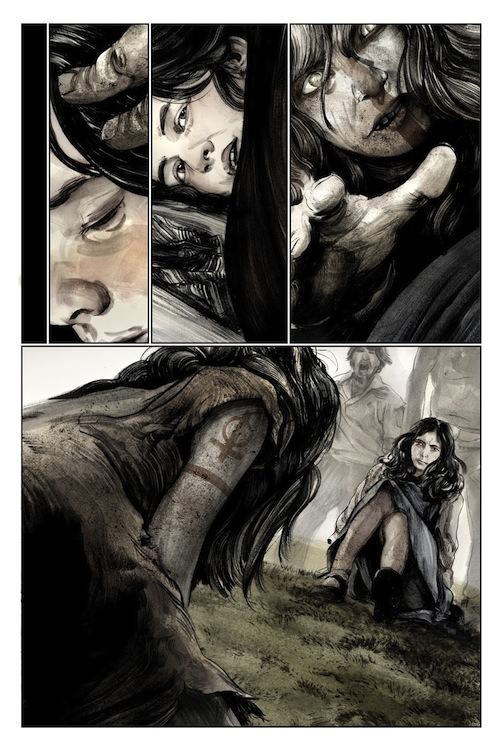

Jumps have their place and their purpose, fair enough, but let’s do more, because the reward for deeper work is really powerful. Comics let you see the whole page at once, so jump scares are kind of spoiled by that. You do have an opportunity at the page turn for a reveal, but the manner by which it comes at the reader does not deliver a jolt or catch you off guard the way a jump scare needs to. So, writers: you’re going to have to come up with something else. You’re going to have to work to scare your readers—sure it’s harder, but if done right, oh so much more effective than any jump scare ever invented. It requires crafting truly captivating characters that you don’t want to see in jeopardy, as opposed to walking tropes that act as redshirts for the death machine. It means inventing new scenarios, new scenes, and constructions that rob the reader/viewer of narrative comforts, but with enough of the basic rules in place to keep them from getting lost.

It’s not at all easy but the creators that succeed are legendary. These narratives beg for repeat reads and watches and you know you’ve got something special the moment it comes to you. Sometimes this can be due to the creator of the piece; other times, it’s the way the ideas are delivered—but this success is always achieved through the use of tone, mood, and place. The importance of all three of these varies in terms of the kind of story you’re telling, but in good horror, all three are essential. It’s great practice to get to know and flex these muscles in a realm where it’s essential so you don’t forget to bring your A-game to the stories they don’t always need to be front and center.

Tone, Mood and Place.

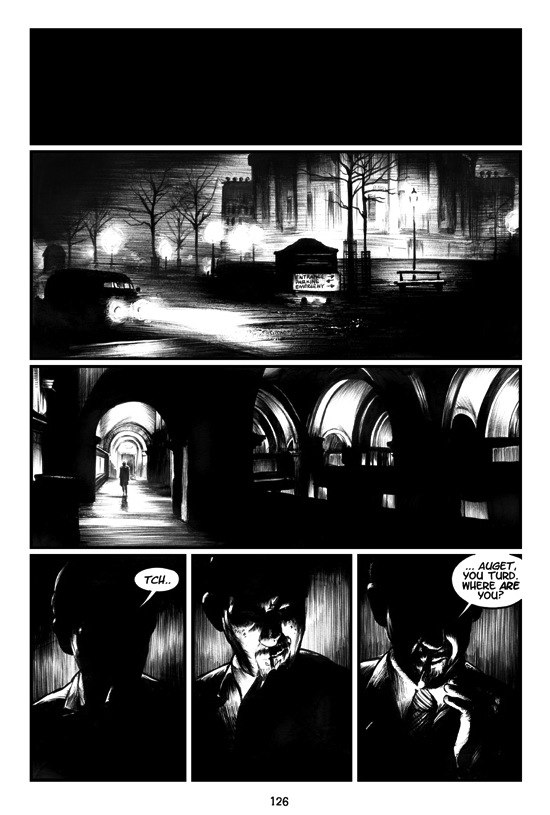

The countermeasure to the classic jump scare is basically the slow build. It’s an old trick from P.T. Barnum: condition your audience towards the mood you wish them to feel, so that triggering that mood becomes easier. In other words, make them come to you. A great example of this strategy in film is Kubrick’s adaptation of The Shining; in comics, it could be Jamie Delano’s Hellblazer, or even Daniel Clowes’ Eightball. Each of these examples basically start you on a path towards a place, using mood and tonal cues in such a way that even mundane or normal threats inside that place are instantly magnified. A couple of twins standing in a hall is quirky and potentially cute. A couple of twins in a hallway in The Shining is terrifying because of Kubrick’s use of sound, music, and slow mood- and world-building. By the time you get to the girls, you’re already conditioned to not find them cute. Those old Hellblazer comics were supremely disturbing in a classical EC Comics kind of way both because Delano’s expert writing and John Ridgeway’s terrifying drawings. They weren’t an orgy of blood and guts, they were just creepy.

The countermeasure to the classic jump scare is basically the slow build. It’s an old trick from P.T. Barnum: condition your audience towards the mood you wish them to feel, so that triggering that mood becomes easier. In other words, make them come to you. A great example of this strategy in film is Kubrick’s adaptation of The Shining; in comics, it could be Jamie Delano’s Hellblazer, or even Daniel Clowes’ Eightball. Each of these examples basically start you on a path towards a place, using mood and tonal cues in such a way that even mundane or normal threats inside that place are instantly magnified. A couple of twins standing in a hall is quirky and potentially cute. A couple of twins in a hallway in The Shining is terrifying because of Kubrick’s use of sound, music, and slow mood- and world-building. By the time you get to the girls, you’re already conditioned to not find them cute. Those old Hellblazer comics were supremely disturbing in a classical EC Comics kind of way both because Delano’s expert writing and John Ridgeway’s terrifying drawings. They weren’t an orgy of blood and guts, they were just creepy.

Clowes certainly does this well—he’s perhaps better than anyone else in terms of mood and place. I’d say he is the most David Lynchian of any modern day comics creators, in this way. The angles, the settings, and the characters are stiff and off-putting, like mannequins in your bedroom. He doesn’t need to try and shock you with classic horror crutches like gore or close-ups of screaming faces, because his use of mood and pacing more than does the trick. Suddenly, normal events like a kiss, or making eggs, or walking down an alley takes on a whole new tone and feel in the world that he’s constructed. The mood he creates informs the action, and takes a lot of the burden off the action to convey the situation. It’s essentially bringing a whole string section into your narrative symphony where one may have been lacking before. It helps you make better music and makes the use of these tools and tricks an elegant and informed choice, rather than a default due to ignorance, lack of practice, or absence of ability.

One important aspect to is to remind yourself as the storyteller to think about the place you’re in, in terms of the size, scale, and scope. Are there dead-end hallways, small cramped cupboards? Long, darkly lit corridors or weirdly constructed bedrooms? Think about how the space and setting can be made to contribute to the overall arc of your story. Is being trapped in small, damp cabin better than in a large, darkly lit mansion? Depends on what you’re doing. One notion I return to often is ascribing character to your place, effectively making the house or town or spaceship or whatever a character unto itself. In Twin Peaks, it’s the woods; in 2001, it’s the Discovery One (and its HAL 9000 computer); in The Shining, it’s the Overlook Hotel, etc… Thinking of places in the same way one thinks of character opens up a tremendous fount of potential and can add a whole new layer to your spooky narrative onion.

Character, Character, Character.

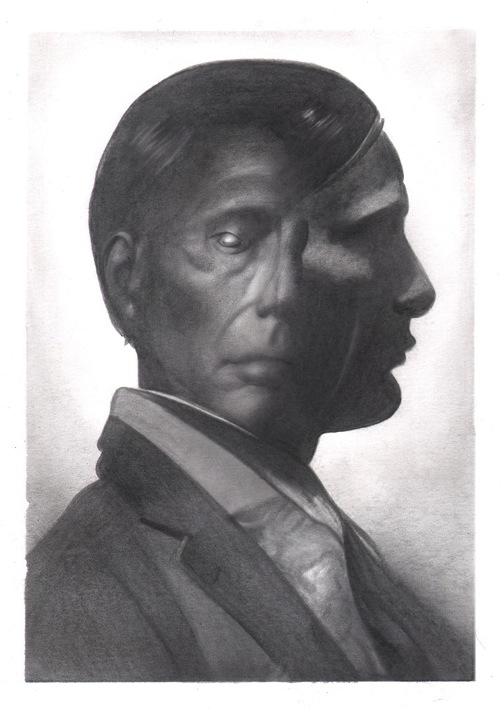

Like any romance, or tragedy, or really any tale worth reading, the substance of the story lives and dies with the characters. As a creator, you absolutely have to pull off the seemingly impossible magic trick of making up an actual living human being, and have the ability to look upon your marks and lines and become emotionally invested in them as if they were also real living people. One reason this works is because emotion happens only in the reader’s head. You can’t grab it, put a collar on it and take it for a walk. It’s not out there to be found, it’s inside to be triggered. As a reader, viewer, or audience member, the people you see and encounter, whether real or not, all go to the same place in your head—so on a certain level it doesn’t matter if you’re looking at a photo, a drawing, or an actual person (at least not to the brain thing locked inside your windowless skull). So as a storyteller, all you really have to accomplish is to paint enough emotionally rich triggers into your characters to fool the brain into investing in them emotionally. You pull this off, the rest is easy—a great set of characters sitting around a table chatting is ten times more interesting to a reader than flat characters in a brilliantly crafted plot. One of the most brilliantly painted modern devils is the character of Hannibal Lecter, and in my book, specifically Bryan Fuller and Mads Mikkelsen’s Hannibal from the TV series. They craft the character beyond the sniffing deranged extremist made famous by Anthony Hopkins and make of him a creature unknowable in human form. His is a perfect blend of compelling magnetism, and terrible violence, a chess-playing tiger in a human suit that is always six steps ahead of you… if you want to really learn how to craft good and terrible creatures in horror, look no further than this.

For horror especially, as a genre that demands an emotional response to threats, making the characters investment-worthy is the whole game. Otherwise it’s just snuff porn, or a bad visual cue for an even worse drinking game. The more your characters ring true, and connect with the readers/viewers, the more we’ll be invested in what happens to them, the greater the tension if something is about to happen, and the harder it will be when something bad happens. We’re living in a time of catchy and often brilliantly clever plot narratives, but less so in terms of character. Worse still, we’re in a cycle of retreading old horror films so that even going into the remake most of us already know the whole film and are really just watching a new rendition of an old song. Comforting, but comfort is not the point when it comes to horror. This is why when you see a spectacularly drawn or filmed narrative with no emotional core, you find yourself usually feeling a bit empty after—your brain just got fed, but your tummy’s still rumbly. A good and well-crafted character will feed the heart and body and mind. Think of it like a girlfriend or boyfriend: it doesn’t matter where you take them for a date, not really, because the point is spending time with them. You don’t care where you are or where you’re going because you got what you want right there in his/her presence. So, when writing a story, especially a spooky one, make your characters like your girlfriend/boyfriend. Then when you put them in jeopardy, you’ve really got something. Anything less is just… less.

Tension Sustainability.

This is the tightrope walk of spooky narratives: sustaining and orchestrating tension. It’s easier in film because you have the benefit of time passing in the form of a moving image, along with sound and music as triggers. In books and comics, you have none of these things. The good news is that you are the scariest person you know. All of you, each of you are. Like building a character, all you have to do is tweak enough of the mind’s desire to see a story unfold, and the mind of the reader will do the rest. We are creatures of stories, almost genetically. We tell each other a story when we first meet each other (Hi, how are you?), we summarize the life of deceased loved ones with stories (eulogies, wakes), we teach and entertain ourselves in story form. So we’re hardwired for narrative and totally looking to be taken advantage of by one. Your reader is a willing participant in this deception, so spend less time trying to sell them something they’ve already bought into just by being there in the first place, and take that advantage and turn it back on them.

One of the most brilliant moments I ever had was talking with John Landis at Comicon years ago as he was raving about how brilliant Tobe Hooper’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre was as a piece of horror cinema. We think we’ve seen a gore fest of murdery horror, but nearly every act of violence occurs off-screen. Which is why it’s so horrific. Leatherface doesn’t go to work on someone in the room with you, he drags the victim off and slams the door, leaving you to sit there alone imagining what’s happening on the other side of that door… and that is SO much worse than anything he could ever show you. The masterstroke of good horror storytelling is letting the audience or readers scare themselves. Alfred Hitchcock pointed to its value most expertly in the famous scenario where he describes two people sitting at a table, talking. It can be engaging, or it can be dull and boring. Put a ticking bomb underneath that table and it can never be boring. One way is a congressional oversight discussion, the other is Han Solo and Greedo chatting in the pub before everything goes boom. Your audience, no matter how wonkish, will always prefer the latter.

The First Rule of the Doctor? The Doctor Lies.

This point comes out of the aforementioned Hooper story, and in comics and prose, is SO ESSENTIAL. In most circumstances, the author or director of a piece of story needs to be trusted in order for it to work. You need to believe he/she knows what they’re doing, and are taking you to a worthy place…otherwise it’s time to check your texts or scan emails, or get a snack. In horror, though, distrust of the author/director can be the key to setting the proper mood, and developing a tone that terrifies. With it, all the other stuff we have talked about above can come to life in ways surprising even to the author. Missing this means having to do a lot more work individually in these areas to make the story function.

On an instinctual level, humans are predatory, highly perceptive creatures, and when there’s a tickle in the bushes, our whole body wakes up to meet what may be there. We become more alert when a narrative trigger tickles our frog brain, telling us to stay frosty until the danger/prey is identified and dealt with in some form. But this state of heightened alertness is not perpetually sustainable and can be exhausted. Think of it like big booming crashes in an orchestra—they’re most effective when saved for those climactic moments when they work best. In the case of the untrustworthy narrator, the device works best when unexpected. So be conscious of your audience’s distrust as a creator—earn it, spend it, and buy it back again.

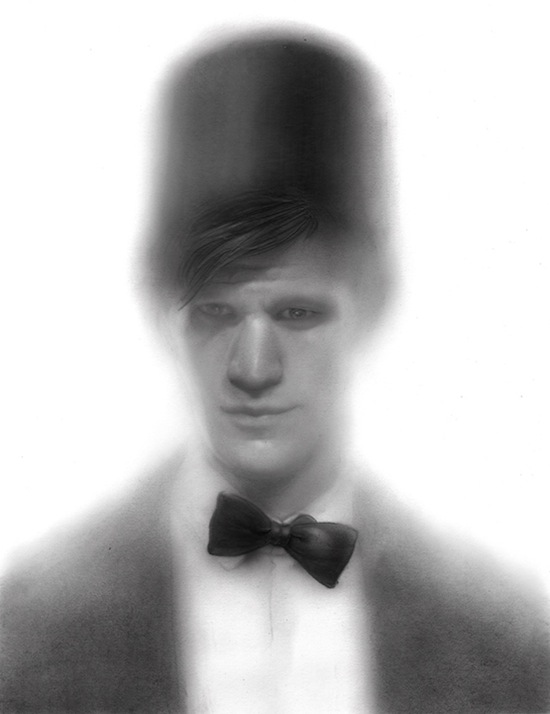

While Doctor Who has always carried its hefty doses of horror, it has reached all new levels of it under Moffatt’s run on the series—much to my own personal delight. Moffatt, coming from a comedy background, understands the essential power of timing and twists. Comedy and horror are, after all, kissing cousins and use a lot of the same tools to execute their aims. Laughing is, in many ways, an automatic response to sudden change or something scary. And you need to be mindful of this joy/fear combo; otherwise, your story is just going to be horrible rather than horror. Twin Peaks, to cite one example, works because it swings between these two poles so well. What Moffatt achieves in his iterations of the Doctor (whether it’s Matt Smith’s nutty professor-ish character or Peter Capaldi’s angry, demented magician) is something similar to Fuller’s Hannibal: a character that is at once wholly attractive and compelling and completely, sometimes terrifyingly unpredictable. He’ll lie to you, abandon you in a state of near-death, and swoop in at the last to rescue you from the consequences. He is a living roller coaster in humanesque form, and is able to deftly move from humor to horror and back again in three lines of dialogue. It is wholly worth watching and studying how these characters are written and how best to bring those qualities over to your own. We don’t prefer beef bourguignon over a can of Dinty Moore stew because fancy people tell us we should; we do so because one is better than the other and we know it. You don’t have to be a genius to spot good quality storytelling, but you do have to be a dum-dum to miss it. The Doctor is a more compelling and attractive character when he’s at his wildest and least trustworthy. As well he should be. Learn to be dangerous.

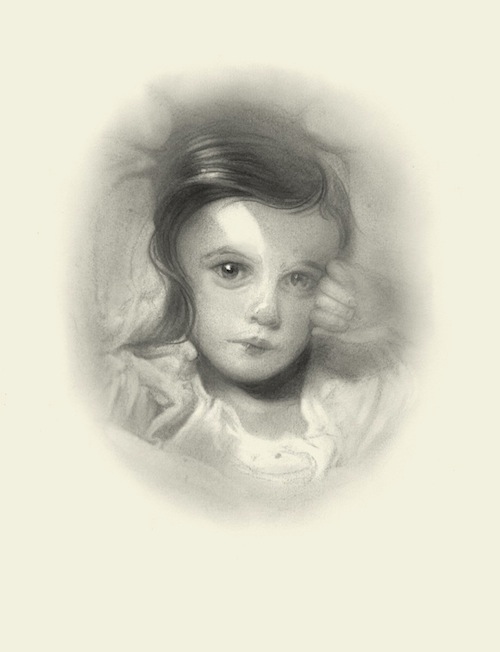

The Familiar is What’s Scary

If an element of horror (a monster, a villain, a setting, etc.) is familiar enough to be identifiable right away, at least in part, it has the potential to be far more disturbing than something completely alien and crazy. The mind is a sorter and cataloguer. It organizes and references past encounters with present ones at lightening speed as a basic survival mechanism. It wants to make sense of things. So the less crazy an image is, the more scary it can be. Cthulhu is freaky because it looks a lot like an octopus head. If it were a ball of spaghettied lights in 7th dimensional undertones, the mind would spend so much time just trying to understand what it’s seeing, it would stop the story until it did. And in comics, if you’re stopping dead by accident, you’re losing. A giant vampire hissing at you in a room is far less eerie than a harmless-looking man in his pajamas standing in the same room who just happens to be floating an inch off the ground. The subtle tricks boom the loudest when attended to and presented in the most simple and elegant ways.

This is largely why I so very much love a good ghost story over any other kind of horror: ghost stories demand a level of elegance and grace and subtlety that other genres don’t. Ghost visitations are private, personal, intimate encounters—the kind you don’t get in more spectacle-driven narratives (say, someone letting a hungry tiger loose in a crowded shopping mall). There’s no place to run from a ghost because ghosts can be everywhere. Hiding under your sheets is the most common response to them, but it belies the point of their power: even in the familiar safety of your bed, they live. Basically the notion here is to craft a singular thing, a concise and essential monster that we know just enough about to be afraid of. Like in politics the tried and true rule applies: if you’re explaining, you’re losing.

Less is More

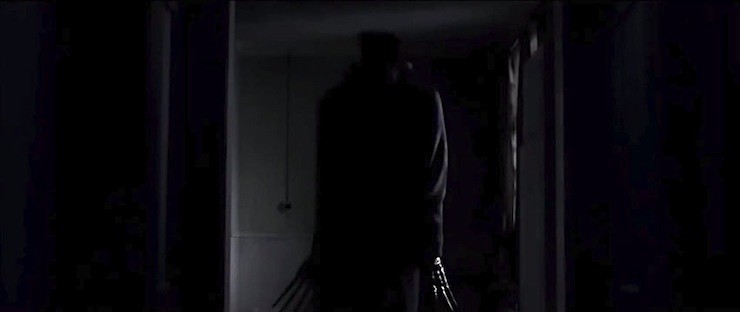

The main reason things are scarier at night is because we can see them less clearly. It’s an animalistic response to the unknown, and here is exactly where you want to plant your flag if you’re crafting a spooky narrative. Personally, I have almost always been disappointed by full reveals of monsters or threats—they always become immediately smaller and containable once revealed. The moment when we see the weird underground cannibal hillbillies in The Descent, the goofy clown face guy in Sinister, or even the room of skeletons in The Shining—these scenes, by revealing their threats so clearly, essentially turn on the overhead lights in a once dark and quiet room. What happens in our brain is that our predator’s perception has now become satisfied by beholding its prey, and all the drama stops. To bring up Tobe Hooper again, in Texas Chainsaw Massacre we never really see a direct gory murder, it always happens off-screen, around the corner or behind the slammed door. The alien in Alien is far scarier as teeth and a tail and a clawed hand than it ever is as a fully-formed creature. It becomes spectacle rather than something more subtle.

Crafting your narrative according to this principle is basically an act of going to the edge of the diving board, and doing all manner of acrobatics there without ever falling into the pool. You want to tickle but never grab. Most recently (and probably amongst all of cinematic history), The Babadook does this better than most. It is an entirely elegant, heartfelt, terrifying story that is at its heart simply a story about how a woman and her son process the grief at the loss of their husband/father. The Babadook is that grief, that regret made manifest. It comes at night, it comes in the shadows. Even when it stands before you fully revealing itself, you can barely distinguish it from the dark that surrounds it. It is a near perfect, if not entirely perfect film in terms of execution, subverting and possibly surpassing its own genre in the process.

A thing that talks to you from the unlit closet is a thing you listen to, much more than if it’s sitting across the table from you at breakfast. The secret truth behind good horror comes from an understanding of our flight/fight response as perceivers. We are trying, as storytellers, to tickle a very particular and basic part of our minds when we spook our audience. This is why so much horror declines into gore or shock, as these are inarguably fast and efficient ways to trigger our lizard brains into leaping off the rock… or out of our seats. The trick we want to achieve, though, is to provoke a reaction but keep the lizard on the rock. We want to tease out that part of our audience’s minds but not chase them away with it. Remember, the more you show, the less there is to imagine—and horror lives and dies in the imagination. The job of a storyteller is then to provide enough space and the trigger, then let the audience fill in the rest with their own terrors. Anything less than that falls flat or turns to schlock.

Here’s the thing that is most often misunderstood about what horror does and doesn’t do: fear is not a cause, but a response. Being afraid to be afraid actually creates a more fearful existence. Engaging with it, wrestling with it, and coming out from under it makes us stronger. We’re a species designed for this exact arc, our survival was literally based upon this notion. Its negative side effects are clear and entirely evident, but unfortunately we have allowed these negatives aspects to occupy all the conversation around how we approach fearful things, blotting out any of the benefits. We live in a safer world than our forebearers, and overall this is a very good thing, of course; but when it comes to the stories we share and create, it has made us weaker in terms of what we gain from their spooky lessons.

This is again not to say that scary things are for everyone. While I am a big fan of horror and scary stories for kids (as laid out in my previous article), forcing scary things on someone not inclined to enjoy them is terrorizing. When it comes to your own kids, you have to read the room. But don’t be afraid to be afraid from time to time. Remember, no matter how scary a movie or a book may be, it’s ability to scare ends at the movie theater doors or the end of the novel. It’s up to you whether you want to take that disturbance further, and you’ll be better equipped in other areas of your life by learning the ability to deal with fear in the relative safety of fictional narratives, rather than in, say, real life. The point is, overall, to have fun and to delight in the odd and mysterious things in life rather than live in fear of them. Whether you’re a creator or a consumer of stories, your experience in making and enjoying all stories is only enhanced by familiarity with some of the basic rules and strategies found in horror. Making art and telling stories demands the breaking of boundaries and of testing yourself, and to learn a rule and decide to ignore it is a stronger act than to ignore a rule or a potential tool because you aren’t familiar with it. Find the limits, push them, go too far and race back in. There are monsters at the edge of the map, but there’s also adventure there, too.

All artwork by Greg Ruth.

The article was originally published in June 2015 on Muddy Colors.

Greg Ruth has been working in comics since 1993 and has published work for The New York Times, DC Comics, Paradox Press, Fantagraphics Books, Caliber Comics, Dark Horse Comics and The Matrix. He has shown his paintings in New York, Houston, and Baltimore, and he also exhibited a series of murals at New York’s Grand Central Terminal in 2002.